Post by Nadica (She/Her) on Aug 3, 2024 21:34:52 GMT

Shadow left by COVID-19 pandemic on the future - Republished Aug 1, 2024

The rapid global spread of vaccinations for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the development of effective anti-COVID-19 drugs, and the establishment of treatment for preventing and managing severe cases have become great game changers in bringing the COVID-19 pandemic to an end, leading us into a life of coexistence with COVID-19, namely “with COVID-19 era”. Now is the time to look back and examine what happened during the COVID-19 pandemic, how healthcare, society, and culture were affected, and what problems have been left for the future.

In 2020, in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was reported that the COVID-19 virus utilizes ACE2 as a receptor when infecting host cells [1]. Because there were earlier experimental studies in which ARBs and ACE inhibitors increased ACE2 expression in animal tissues, some researchers considered that COVID-19 infectivity may be augmented in patients with hypertension or heart failure who are taking these drugs [2]. Based on this hypothesis, concerns that ARBs and ACE inhibitors might be risk factors for COVID-19 infection and worsening spread through SNS and some mass media. In fact, during the first wave of COVID-19 infections in the Europe, not a little number of patients self-discontinued taking ARBs and ACE inhibitors. Therefore, the Japanese Society of Hypertension and Japanese Circulation Society, as well as the European Society of Cardiology, European Society of Hypertension, and American Heart Association released urgent statements as academic specialists that ARBs and ACE inhibitors prescribed under the guideline-directed medical treatment should not be discontinued [3, 4]. Thereafter, numerous observational and registry studies conducted in countries around the world, including Japan, showed that ARBs and ACE inhibitors had neutral or negative impact on infectivity or severity of COVID-19 [5, 6], confirming that these statements were correct. Kai et al. conducted a systematic review of animal studies including 88 articles and found that administration of ARBs and ACE inhibitors, as well as other antihypertensive drugs, rarely increased ACE2 expression or activity in the tissues, including the hearts, kidney, arteries, and lungs, of the intact animals and animal models of hypertension or heart, kidney, and vascular diseases [7]. In this issue of Hypertension Research, Natsume et al. reported that the number of ARB and ACE inhibitor prescriptions did not decrease, but rather increased, during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan, based on the Japanese National Database (NDB) Open Data [8]. This finding suggests the importance of academia to take a decisive stance in pointing in the right direction based on scientific evidence and expert consensus to the public and practitioners in emergency situations such as COVID-19 pandemics, and is proof that proper medical care has been achieved in Japan during the pandemic.

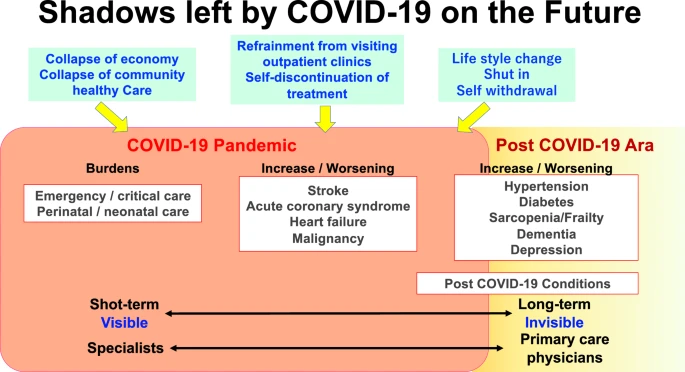

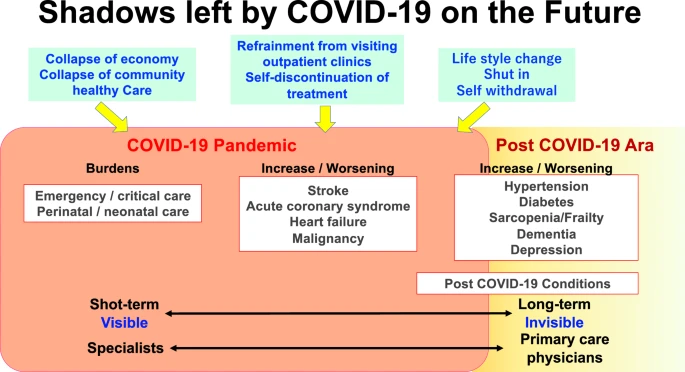

On the other hand, an increase in blood pressure levels was shown in Japan despite the continuation of appropriate antihypertensive drug therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic [9]. In addition to anxiety about the pandemic, the reasons for blood pressure elevation may be related to decreased adherence to medication or failure to adjust treatment due to refraining from outpatient visits (Figure 1). In addition, adverse influences on lifestyle habits, such as decreased physical activity due to “Hikikomori” stay-at-home, increased consumption of salt-rich preserved and instant foods, decreased consumption of fresh vegetables, and increased drinking at home, may also be involved. Even after the COVID-19 pandemic has come to end, many people, especially the elderly, remain inactive physically and socially. These factors may lead to increases in hypertension, diabetes, sarcopenia, frailty, depression, and cognitive decline, resulting in increased cerebrovascular events, not only during the pandemic but also in the COVID-19 era.

In COVID-19-infected patients, post-COVID-19 conditions (PCC) such as shortness of breath, anxiety, muscle pain/weakness, depression, and fatigue often persist for more than one year, regardless of the presence of symptoms or severity during the acute phase. A recent cohort study using a large commercial insurance database in the United States found a twofold increase in the risk of cardiovascular and respiratory disease and a doubled mortality with 16.4 deaths per 1000 persons during a one-year follow-up period [10]. During the pandemic, mainly specialists in emergency medicine, perinatal care, cardiovascular disease, and respiratory disease, etc., bore a heavy burden directly and indirectly caused by COVID-19 (Graphic Abstract). For a long time to come with COVID-19 era, primary care physicians will be the gatekeepers of not only hypertension, diabetes, sarcopenia, frailty, cardiovascular diseases and mental diseases related to disordered lifestyle and psychological damages caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, but also PCC and cardiovascular diseases and respiratory diseases as COVID-19 sequelae. Academia, specialists, and primary care physicians should come together to confront the shadows left by COVID-19 pandemic in the future.

References

1. Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–80.e8.

2. Esler M, Esler D. Can angiotensin receptor-blocking drugs perhaps be harmful in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hypertens. 2020;38:781–2.

3. Japanese Society of Hypertension. Information of COVID-19. www.ipnsh.jp/corona.html. Accessed 7 June 2020.

4. Japanese Circulation Society. Information on COVID-19 in cardiology. www.j-circ.or.jp/covid-19/. Accessed 7 June 2020.

5. Kai H, Kai M. Interactions of coronaviruses with ACE2, angiotensin II, and RAS inhibitors—lessons from available evidence and insights into COVID-19. Hypertens Res. 2020;43:648–54.

6. Shibata S, Arima H, Asayama K, Hoshide S, Ichikawa A, Ishimitsu T, et al. Hypertension and related diseases in the era of COVID-19: a report from the Japanese Society of Hypertension Task Force on COVID-19. Hypertens Res. 2020;43:1028–46.

7. Kai H, Kai M, Niiyama H, Okina N, Sasaki M, Maeda T, et al. Overexpression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 by renin-angiotensin system inhibitors. Truth or Myth? A systematic review of animal studies. Hypertens Res. 2021;44:955–68.

8. Natsume S, Satoh M, Murakami T, Sasaki M, Metoki H, The trends of antihypertensive drug prescription based on the Japanese national data throughout the COVID-19 pandemic period. Hypertens Res. 2024. doi.org/10.1038/s41440-024-01706-7.

9. Satoh M, Murakami T, Obara T, Metoki H. Time-series analysis of blood pressure changes after the guideline update in 2019 and the coronavirus disease pandemic in 2020 using Japanese longitudinal data. Hypertens Res. 2022;45:1408–17.

10. DeVries A, Shambhu S, Sloop S, Overhage JM. One-year adverse outcomes among US adults with post–COVID-19 condition vs those without COVID-19 in a large commercial insurance database. JAMA Health Forum. 2023;4:e230010.

The rapid global spread of vaccinations for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the development of effective anti-COVID-19 drugs, and the establishment of treatment for preventing and managing severe cases have become great game changers in bringing the COVID-19 pandemic to an end, leading us into a life of coexistence with COVID-19, namely “with COVID-19 era”. Now is the time to look back and examine what happened during the COVID-19 pandemic, how healthcare, society, and culture were affected, and what problems have been left for the future.

In 2020, in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was reported that the COVID-19 virus utilizes ACE2 as a receptor when infecting host cells [1]. Because there were earlier experimental studies in which ARBs and ACE inhibitors increased ACE2 expression in animal tissues, some researchers considered that COVID-19 infectivity may be augmented in patients with hypertension or heart failure who are taking these drugs [2]. Based on this hypothesis, concerns that ARBs and ACE inhibitors might be risk factors for COVID-19 infection and worsening spread through SNS and some mass media. In fact, during the first wave of COVID-19 infections in the Europe, not a little number of patients self-discontinued taking ARBs and ACE inhibitors. Therefore, the Japanese Society of Hypertension and Japanese Circulation Society, as well as the European Society of Cardiology, European Society of Hypertension, and American Heart Association released urgent statements as academic specialists that ARBs and ACE inhibitors prescribed under the guideline-directed medical treatment should not be discontinued [3, 4]. Thereafter, numerous observational and registry studies conducted in countries around the world, including Japan, showed that ARBs and ACE inhibitors had neutral or negative impact on infectivity or severity of COVID-19 [5, 6], confirming that these statements were correct. Kai et al. conducted a systematic review of animal studies including 88 articles and found that administration of ARBs and ACE inhibitors, as well as other antihypertensive drugs, rarely increased ACE2 expression or activity in the tissues, including the hearts, kidney, arteries, and lungs, of the intact animals and animal models of hypertension or heart, kidney, and vascular diseases [7]. In this issue of Hypertension Research, Natsume et al. reported that the number of ARB and ACE inhibitor prescriptions did not decrease, but rather increased, during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan, based on the Japanese National Database (NDB) Open Data [8]. This finding suggests the importance of academia to take a decisive stance in pointing in the right direction based on scientific evidence and expert consensus to the public and practitioners in emergency situations such as COVID-19 pandemics, and is proof that proper medical care has been achieved in Japan during the pandemic.

On the other hand, an increase in blood pressure levels was shown in Japan despite the continuation of appropriate antihypertensive drug therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic [9]. In addition to anxiety about the pandemic, the reasons for blood pressure elevation may be related to decreased adherence to medication or failure to adjust treatment due to refraining from outpatient visits (Figure 1). In addition, adverse influences on lifestyle habits, such as decreased physical activity due to “Hikikomori” stay-at-home, increased consumption of salt-rich preserved and instant foods, decreased consumption of fresh vegetables, and increased drinking at home, may also be involved. Even after the COVID-19 pandemic has come to end, many people, especially the elderly, remain inactive physically and socially. These factors may lead to increases in hypertension, diabetes, sarcopenia, frailty, depression, and cognitive decline, resulting in increased cerebrovascular events, not only during the pandemic but also in the COVID-19 era.

In COVID-19-infected patients, post-COVID-19 conditions (PCC) such as shortness of breath, anxiety, muscle pain/weakness, depression, and fatigue often persist for more than one year, regardless of the presence of symptoms or severity during the acute phase. A recent cohort study using a large commercial insurance database in the United States found a twofold increase in the risk of cardiovascular and respiratory disease and a doubled mortality with 16.4 deaths per 1000 persons during a one-year follow-up period [10]. During the pandemic, mainly specialists in emergency medicine, perinatal care, cardiovascular disease, and respiratory disease, etc., bore a heavy burden directly and indirectly caused by COVID-19 (Graphic Abstract). For a long time to come with COVID-19 era, primary care physicians will be the gatekeepers of not only hypertension, diabetes, sarcopenia, frailty, cardiovascular diseases and mental diseases related to disordered lifestyle and psychological damages caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, but also PCC and cardiovascular diseases and respiratory diseases as COVID-19 sequelae. Academia, specialists, and primary care physicians should come together to confront the shadows left by COVID-19 pandemic in the future.

References

1. Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–80.e8.

2. Esler M, Esler D. Can angiotensin receptor-blocking drugs perhaps be harmful in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hypertens. 2020;38:781–2.

3. Japanese Society of Hypertension. Information of COVID-19. www.ipnsh.jp/corona.html. Accessed 7 June 2020.

4. Japanese Circulation Society. Information on COVID-19 in cardiology. www.j-circ.or.jp/covid-19/. Accessed 7 June 2020.

5. Kai H, Kai M. Interactions of coronaviruses with ACE2, angiotensin II, and RAS inhibitors—lessons from available evidence and insights into COVID-19. Hypertens Res. 2020;43:648–54.

6. Shibata S, Arima H, Asayama K, Hoshide S, Ichikawa A, Ishimitsu T, et al. Hypertension and related diseases in the era of COVID-19: a report from the Japanese Society of Hypertension Task Force on COVID-19. Hypertens Res. 2020;43:1028–46.

7. Kai H, Kai M, Niiyama H, Okina N, Sasaki M, Maeda T, et al. Overexpression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 by renin-angiotensin system inhibitors. Truth or Myth? A systematic review of animal studies. Hypertens Res. 2021;44:955–68.

8. Natsume S, Satoh M, Murakami T, Sasaki M, Metoki H, The trends of antihypertensive drug prescription based on the Japanese national data throughout the COVID-19 pandemic period. Hypertens Res. 2024. doi.org/10.1038/s41440-024-01706-7.

9. Satoh M, Murakami T, Obara T, Metoki H. Time-series analysis of blood pressure changes after the guideline update in 2019 and the coronavirus disease pandemic in 2020 using Japanese longitudinal data. Hypertens Res. 2022;45:1408–17.

10. DeVries A, Shambhu S, Sloop S, Overhage JM. One-year adverse outcomes among US adults with post–COVID-19 condition vs those without COVID-19 in a large commercial insurance database. JAMA Health Forum. 2023;4:e230010.